What is Environmental Racism?

The pattern is increasingly familiar. Black, Indigenous, and Latinx groups are disproportionately affected by COVID-19, police brutality and chronic illness. These groups are also more likely to live near polluting infrastructure or in areas affected to a greater extent by climate change and are less likely to be awarded resources to solve these issues. Environmental racism refers to policies, regulations, or corporate decisions that either intentionally or unintentionally target communities of color for environmentally damaging land uses. Individuals affected by environmental racism lack access to safe shelter, healthy food, or clean drinking water and endure chronic diseases at a disproportionate rate to the rest of the population.

Environmental justice refers to the movement aimed to counteract this inequity. The EPA describes it as: “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies.”

Environmental racism and intersectionality have been awarded recent attention due to the BLM movement and calls for racial justice globally. The communities of color I refer to in this article are Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities. I am using “Latinx” instead of Latino/Latina as a gender-neutral term. Please also note that this piece specifically focuses on environmental justice within the United States.

The History

The environmental justice movement was born in the 1960s and was aimed towards erecting rights, protections and equalities for all people within the environmental movement.

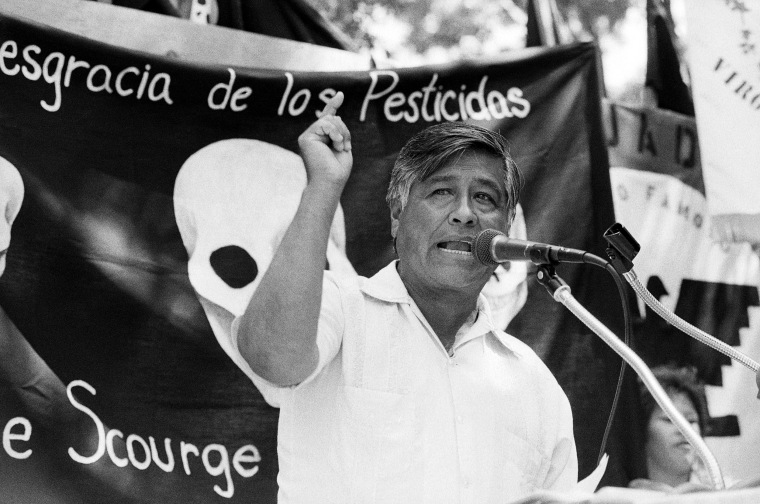

During the 1960s, small protests held largely by Black and Latinx communities started to gain momentum nationally. Latinx farm workers were led by Cesar Chavez in fighting for protections against pesticides used in San Joaquin’s farming valley. In 1967, Black students in Houston fought against a city garbage dump that had killed a child. Smaller protests like these went largely unnoticed until 1982, when North Carolina announced its plan to move soil contaminated with PCB, an industrial toxin, from 210 miles of roadways to a landfill in Warren County. The county was one of the few in NC that was predominately Black, leading to protests that gathered national media attention. Despite the public uproar, the toxins were buried in county’s landfill.

The following year, the General Accounting Office released a report noting that hazardous waste dumping sites in three southeastern states were disproportionately located near Black communities. The Church of Christ confirmed this in a 1987 report which found 3 out of 5 Black and Latinx Americans lived near a toxic waste site. The National Center for Environmental Assessment found that compared to Whites, Black people had 1.5 times more particulate exposure, while Hispanics had 1.2 times more exposure. People in poverty had 1.3 times more exposure than people not in poverty.

Leaders of the environmental justice movement sought allyship from ten powerful environmental organizations (called the “Group of Ten”*) by sending a publicized letter in 1990, accusing these groups of hiring discrimination, lack of diversity on their boards, making decisions for black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) without their input, and accepting funding from major polluting corporations (i.e. Exxon, IBM, Coca-Cola). A 2014 study by Green 2.0 found that people of color made up only 12-16% of the staff of environmental nonprofits, foundations, and agencies. In 2018, this number increased only to 20% for the 40 largest green nonprofits. Without adequate representation, Black, Indigenous, and Latinx groups will continue to have a disproportionate share of environmental destruction and resulting health and social consequences in the United States.

*The Group of Ten includes these organizations: Defenders of Wildlife, Environmental Defense Fund, Greenpeace, the National Audubon Society, the National Wildlife Federation, Natural Resources Defense Council, The Nature Conservancy, Sierra Club, The Wilderness Society, and World Wildlife Fund. Read the full letter here.

The Root Causes

Pointing out a singular cause of environmental injustice would be impossible — it is rooted in political, social, and economic behaviors and systems that have perpetuated colonialism and racist ideologies. It is difficult to separate issues of poverty and race completely within the environmental sphere as these two factors are often correlated. We can, however, dissect the most likely causes that concentrate the effects environmental injustice.*

*The list below includes causes that apply to most cases today, but does not include issues like redlining, government segregationist housing policies, or other discriminatory practices that have perpetuated the issues of environmental injustice on certain neighborhoods for centuries.

- Intentional Discrimination by Corporations: Corporations pray on communities without the resources to prevent the siting of hazardous infrastructure. These communities are typically poor communities, have majority Black, Latinx or Indigenous populations, or both. In 1984, the consulting firm Cerrell Associates noted that while all socioeconomic groups are against environmental hazards being near their homes, middle and higher class groups have more resources to oppose these hazards and therefore the hazards should be located within poorer communities.

- Regulation and Risk-Management Agencies: Environmental racism may occur as a consequence of neutral-risk management agencies. In order to minimize risk to the greatest number of people, noxious facilities may be placed in areas of low-population density. As a result, poor rural areas may have a disproportionate amount of polluting infrastructure.

- Unequal Enforcement: There has been evidence of reduced enforcement of environmental laws in communities of color and poor communities compared to white, affluent communities. This can occur as a consequence of these two behaviors:

- Unequal Penalties: In a 1992 study, researchers found that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) increased penalties 500% for hazardous waste sites in majority-white communities. Hazardous waste is the pollution type most concentrated in communities of color. Additionally, it took 20% longer to clean up abandoned waste sites in communities of color compared to white communities. A 2005 study found similar circumstances, noting: “We can conclude that whereas facilities in high-percent minority areas tend to violate regulations more often, they receive relatively few notices from the state, and their fines tend to be relatively low.” Read the full studies here: https://www.ejnet.org/ej/nlj.pdf (1992), https://astro.temple.edu/~jmennis/pubs/mennis_pg05.pdf (2005).

- Compliance Bias: Compliance bias is the malpractice by regulators who assume compliance by companies and fail to properly inspect for violations. According to multiple studies, Hispanic and low-income neighborhoods are the most likely to suffer the effects of compliance bias.

- Low Political Power: Community political influence is correlated positively with higher median income, a greater percentage of residents with a high school diploma, a greater percentage of employed residents, and greater voter turnout. As referenced in the Cerrell Report above, toxic infrastructure can be more easily sited in areas with fewer resources, including those with lesser political influence. Plants which are located on the edges of districts or which pollute areas beyond their immediate surroundings place even further difficulties on communities to oppose them or call for proper regulation.

Where Is This Going on Today?

Flint, MI: Flint, Michigan is probably the most infamous case of environmental racism today. The city is 54% Black and over 40% of residents live in poverty. Flint’s water crisis began in 2014 when a Michigan emergency manager decided to switch the city’s main water supply to the Flint River to reduce spending. The river water was never treated to prevent corrosion, allowing harmful contaminants like lead to leach into resident’s water. After dismissing resident’s concerns for over a year, state officials finally admitted there was a contamination problem.

“Given the magnitude of the disaster in Flint, the role that public officials’ decisions played that led to the poisoning of the city’s water, their slow pace at acknowledging and responding to the problem, and the fact that Flint is a city of almost 100,000 people indeed makes this the most egregious example of environmental injustice and racism in my over three decades of studying this issue.”

– Paul Mohai, University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability

Wilmington, CA: There are 6,717 oil and natural gas wells within the Los Angeles basin. Wilmington, located in the southern part of LA county, is 92% Latinx. 78% of the residents make less than $30,000 annually. Compared to West Pico, a neighborhood that is 88% white and where 58% of residents made over $30,000 a year (a 25 minute drive north), residents of Wilmington were five times more likely to have coronary heart disease, ten times more likely to experience chest pain, and more than three times more likely to have dizziness, nausea, or vomiting.

Pipelines: Pipelines across the country are typically blatant examples of environmental racism. The Dakota Access Pipeline, which was recently ordered to shut down, sparked protests in 2016 after the US Army Corps of Engineers approved it’s construction to carry crude oil from North Dakota to Illinois. The pipeline ran under the Missouri River less than 1 mile north of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. The Atlantic Coast Pipeline, which was also recently cancelled after facing extensive delays, was set to run through low-income communities of color and end in the Lumbee Tribe community in NC.

Storm Prevention: Fossil fuels make more severe storms more likely, and people of color are less likely to access resources to prevent destruction or rebuild after severe weather events. Levee boards in New Orleans following Hurricane Betsy were made up of predominantly white residents. Allocation of funding for levees was sent mostly to affluent white neighborhoods instead of low-lying communities of color where levees were already vulnerable. In 2005, these neighborhoods were the hardest hit by Hurricane Katrina and were not considered for redevelopment by city council after the storm (some were instead turned to “green space”).

These are just several examples. Look to Detroit, MI (the most polluted zip code) or Cancer Valley for more.

Threats Right Now

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), was the first major environmental law in the United States. Founded in 1970, it made it necessary to consider the input of communities and the analysis of environmental costs before the approval of new pipelines, factories, drilling, or other major infrastructure projects. Trump recently announced rollbacks to NEPA, calling it the “single biggest obstacle” to major construction projects in the U.S. His new rollbacks not only include cutting the time of reviews significantly, but also removing “climate change” as a consideration in the process.

Gutting NEPA could be disastrous for communities of color. Without the ability to submit effective community input and thorough environmental analyses, Black, Latinx and Indigenous communities already suffering from lack of power in the environment sphere will be silenced even further.

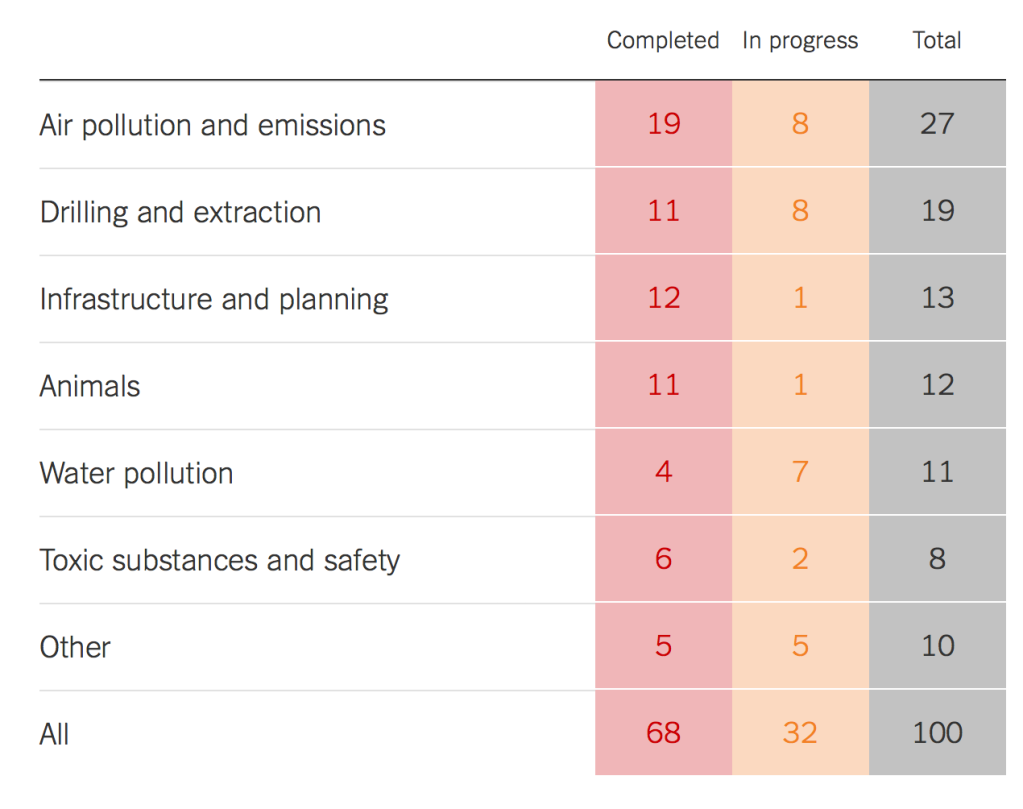

NEPA isn’t the only law in trouble. Trump is on his way to rolling back 100 environmental rules. Over 70 have already been reversed or rolled back, with 30 more in progress. Without these safe guards, already disproportionate effects of polluting infrastructure and climate change will be compounded in communities of color.

Furthermore, we cannot solve the issue of environmental racism without solving other issues faced by vulnerable communities. This includes violence against communities of color, discrimination and pay discrepancies, and unequal access to food and healthcare (amongst many others). Without total systematic change, we can not have sustainability for all people. Without the voices of those most affected, we will fail.

“Climate change is more than parts per million and greenhouse gases. The people who are feeling the worst impacts of climate, their voices have got to be heard.”

– Robert D. Bullard

“Environmental injustice, prejudicial, *&* discrimination defines the black ghetto from its inception since slavery until now!”_-Van Prince

LikeLike

“Environmental racism is Racism period *&*Racism against blacks manifested from the Institution of Slavery In America comprising Reconstruction, Jim Crow Segregation, *&* Affirmative Action.”_Van Prince

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is a fact that George Floyd’s murder by a white racist police don’t mean that all whites are racist because they are not, and there are just as many whites as blacks marching *&* protesting that Black Lives Matter *&* I get that, but what I also get is that George Floyd’s murder isn’t rare but common as white racist police have murdered over thirty blacks in seven years, and all of the wrongs done against blacks manifested from over 300-years of Slavery of Blacks known as the Institution of Slavery=over three centuries of free labor *&* nobody is advocating and demanding *REPARATION FOR SLAVERY* *&* when America is a capitalistic Nation that practice wages for work perform, *&* to think that none marching and protesting never mentioned reparation. Even Tom S., who was running for the 2020 Democratic Nomination advocated Reparation For Slavery,but blacks voted for Joe Biden who was not and is not advocating Reparation for Slavery. I am a black man and I have been in the struggle fighting for freedom, justice, *&* equality for blacks for years, and many people from other races think of blacks as being stupid and not informed for not advocating reparation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It seems all big ideas are always hard to accept, especially in a political realm. I hope that as we continue to fight for the rights and equity of Black lives we can look to our past and both recognize/repair the inequities spanning all social/economic spheres. People always put down what they can’t understand.

LikeLike

Your response is equality for all is great. Thank you!

LikeLike

You are the first person whoever mentioned this post, *&* of all my posts this is the only one others shied away from *&* its logical if someone disagreed with the extent that George Floyd should be honored, but I told it like it is *&* not a soul disagreed with me. Truth-is-truth akin when a defendant is on trial *&* the prosecutor know certain evidence favors the accuse what they do is don’t mention it!

LikeLike

“History is the gateway to all truth undiluted!”_-Van Prince

LikeLike

“History is the cornerstone of mankind and civilization.”__Van Prince

LikeLike